Views: 222 Author: Lake Publish Time: 2026-01-31 Origin: Site

Content Menu

● Foundational Principles: Why Adjustment is Necessary

>> The "Optimum Position" Concept

● The Adjustment Toolkit: Core Maneuvers

>> 1. The Axial Lift: The Primary Adjustment

>> 2. Blade Tip Repositioning: Fine-Tuning the Fulcrum

>> 3. Rotational Adjustment ("Rotational Torque")

>> 4. External Laryngeal Manipulation (ELM) / BURP Maneuver

● Step-by-Step Adjustment Sequence for Direct Laryngoscopy

● Adjustments in Video Laryngoscopy: A Different Paradigm

● Troubleshooting Common Poor Views and Their Adjustments

● The Role of Patient Re-Positioning as an Adjustment

● Safety and Ergonomic Considerations During Adjustment

● Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

>> 1. What is the single most important adjustment to make if I can only see the epiglottis?

>> 3. When should I stop adjusting and just take the laryngoscope out?

>> 4. How do I adjust for a patient with very large or prominent front teeth?

>> 5. Does the adjustment technique differ between an adult and an infant?

The successful use of a laryngoscope hinges not merely on its insertion into the mouth, but on the precise, dynamic adjustments made once it is positioned. A laryngoscope is not a static tool; it is an instrument of fine control. The ability to skillfully adjust a laryngoscope within the confined, complex anatomy of the oropharynx is what differentiates a proficient clinician from a novice. These adjustments are the key to transforming a partial or obscured view into a clear, Grade I visualization of the glottis. This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step guide to the art and science of adjusting a laryngoscope, covering techniques for both direct and video laryngoscopy, common challenges, and the underlying anatomical principles that inform every corrective movement.

Before delving into technique, it is crucial to understand why adjustment is a constant requirement during laryngoscopy. The oropharyngeal cavity is not a fixed tunnel; it is a dynamic space filled with soft, mobile tissues—the tongue, epiglottis, and arytenoids—that can easily fall back into the line of sight. The goal of the laryngoscope is to create and maintain a visual pathway. Initial placement is almost never perfect due to anatomical variation, patient positioning subtleties, and the inherent challenge of operating without direct sight during insertion (for direct laryngoscopy). Therefore, a series of deliberate, learned adjustments are essential to optimize the view.

For both direct and video laryngoscopy, the optimum position is defined by a single outcome: the centered, unobstructed visualization of the glottic opening, including the vocal cords and the anterior commissure. Any adjustment of the laryngoscope should have this as its sole objective. The adjustments themselves are mechanical means to achieve this optical result.

The clinician has a limited set of physical actions to adjust the laryngoscope. Mastery involves knowing which one to apply and in what sequence.

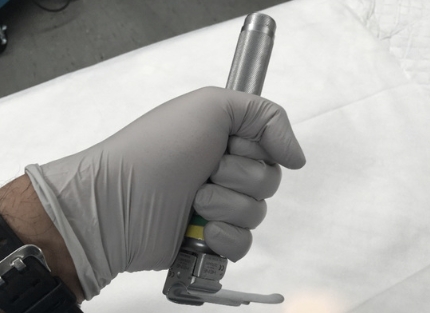

This is the most fundamental and powerful adjustment. It involves lifting the entire laryngoscope along the axis of its handle.

- Mechanism: Increases tension on the hyoepiglottic ligament (for Macintosh blades in the vallecula) or directly on the epiglottis (for Miller blades). This pulls the epiglottis upward and forward, away from the glottis.

- How to Perform: The force should originate from the shoulder and upper arm, with a straight wrist. It is a steady, upward-and-forward lift, not a rocking motion on the teeth.

- When to Use: As the first adjustment if the epiglottis is obscuring the view. Often, simply increasing a tentative lift is all that is needed. In direct laryngoscopy, insufficient lift is the most common cause of failure.

Small movements of the blade tip within the vallecula or beneath the epiglottis can have a dramatic effect.

- Mechanism: Changes the point of applied force on the hyoid complex or the epiglottis.

- How to Perform:

- Advancement/Withdrawal ("In and Out"): If the view is of the esophagus (blade too deep) or only the base of the tongue (blade too shallow), gently withdraw or advance the blade by 0.5-1 cm.

- Lateral Movement ("Side to Side"): If the view is off-center—showing only one arytenoid cartilage—apply gentle lateral pressure with the blade tip to center the laryngeal inlet. For a Macintosh blade, this often means nudging the tip slightly to the patient's right to center the view.

- When to Use: When the lift is adequate but the view is too deep, shallow, or laterally displaced.

This involves applying a subtle clockwise or counterclockwise rotational force to the laryngoscope handle.

- Mechanism: In direct laryngoscopy, this helps to "sweep" the tongue more completely into the left side of the blade's flange, preventing it from herniating back into the visual pathway. In video laryngoscopy, it can help align the camera's perspective.

- How to Perform: With your left hand, gently rotate the handle as if turning a screwdriver, typically in a clockwise direction (blade flange presses left). This must be done while maintaining the axial lift.

- When to Use: When the tongue is persistently obscuring the right side of the view (a very common problem), or when using a hyperangulated video blade to fine-tune the camera angle.

This critical adjustment is performed not with the laryngoscope itself, but with the operator's free right hand or an assistant's hand.

- Mechanism: Physically moves the larynx posteriorly, superiorly, and sometimes to the right, bringing an anterior larynx into better view.

- How to Perform: Apply backward (posterior), upward, and right-sided pressure on the thyroid cartilage (Adam's apple). The optimal spot is found by instructing an assistant to move their fingers while you watch the view improve.

- When to Use: Specifically for an anterior larynx, where despite good technique, the glottis remains hidden behind the tongue base. This is a first-line adjustment for a difficult direct laryngoscopy view.

A systematic approach prevents frantic, uncoordinated movements. The mnemonic L-O-A-D can be helpful:

1. L - LIFT (Optimize Axial Lift): Insert the blade and apply your initial lift. If the view is poor (e.g., only epiglottis), the first and most important adjustment is to increase the lift significantly. Ensure you are lifting along the axis, not rocking.

2. O - OPTIMIZE TIP POSITION: If the lift is strong but the view remains suboptimal, fine-tune the blade tip. Is it too deep (seeing esophagus)? Gently withdraw 1 cm. Is it too shallow? Gently advance. Is the view lateral? Apply gentle lateral tip pressure.

3. A - APPLY ROTATIONAL TORQUE: If the tongue is falling in from the right, apply gentle clockwise rotational torque to the handle to secure it within the flange.

4. D - DIRECT EXTERNAL MANIPULATION (ELM/BURP): If after steps 1-3 the cords are still not visible (a Grade III view), immediately use your right hand to perform ELM. This is often the game-changing adjustment for the difficult airway.

Adjusting a video laryngoscope shares principles with direct laryngoscopy but has unique aspects due to the indirect, screen-based view.

1. The "Screen-as-Guide" Mentality: All adjustments are informed by the live video feed. Your eyes should be on the screen, not your hands.

2. Reduced Force, Increased Finesse: The need for a powerful axial lift is often greatly diminished. The primary goal is to position the camera optimally. Adjustments become more about navigation than forceful displacement.

3. Hyperangulated Blade Specifics: With a sharply curved blade (e.g., GlideScope D-Blade), the adjustment focus shifts.

- Insertion Path: The initial adjustment is to ensure the blade is following the natural curvature of the tongue, not "hanging up" on the palate. A slight withdrawal and re-advancement with a more posteriorly directed path may be needed.

- The "Withdrawal-to-Improve" Phenomenon: Unlike direct scopes, the best view with a hyperangulated laryngoscope is often achieved by withdrawing the blade slightly after deep insertion, which pulls the camera back to a wider-field, less tissue-obstructed vantage point.

- Avoid "Blade-to-Screen" Movement: Do not lift the handle toward the screen; this buries the camera in the tongue base. Keep the handle low, often parallel to the chest.

4. Use of a Stylet as an Adjustment Tool: The endotracheal tube with a pre-shaped stylet becomes an extension of your adjusting capability. If the tube tip is visible on screen but cannot be directed into the glottis, you can adjust its shape or use it to gently lift the epiglottis ("epiglottic lift") under direct vision.

- View: Only the epiglottis (Grade IIa).

- Primary Adjustment: Increase Axial Lift. The blade is likely in the correct place (vallecula) but with insufficient lifting force.

- Secondary: Ensure the blade tip is securely in the vallecula and not slipping off.

- View: Only the arytenoids or the posterior cartilages (Grade IIb/III).

- Primary Adjustment: External Laryngeal Manipulation (ELM/BURP). The larynx is too anterior.

- Secondary: Consider a slight withdrawal of the blade tip (may be too deep) and reassess.

- View: Esophagus (a pink, circular hole).

- Primary Adjustment: Withdraw the blade deliberately by 1-2 cm. The blade is too deep and has passed the larynx.

- View: Tongue obscuring the right side.

- Primary Adjustment: Apply Rotational Torque (clockwise) to better control the tongue within the flange.

- View: "Red Out" or no identifiable structures (Video Laryngoscope).

- Primary Adjustment: Withdraw the blade. The camera is pressed directly against mucosa (tongue or pharyngeal wall). Withdraw until anatomy appears.

- Secondary: Ensure the lens is not fogged or soiled.

Sometimes, the best adjustment to the laryngoscope is an adjustment to the patient. If optimal views cannot be achieved, re-check and optimize:

- Sniffing Position for Direct Laryngoscopy: Ensure neck flexion and head extension are adequate.

- Neutral Position for Video Laryngoscopy: For some hyperangulated scopes, a neutral head position is better. A slight head lift ("ramping") with blankets under the shoulders and occiput can be particularly helpful for obese patients to align the ear and sternal notch horizontally.

- Patience Over Force: Adjustments should be deliberate, not jerky or forceful. Excessive force causes trauma, damages teeth, and fatigues the operator.

- Protect the Teeth: Constant awareness of the upper incisors. The laryngoscope should never lever against them. Use a plastic tooth protector if needed.

- Know When to Stop and Re-oxygenate: If after 20-30 seconds of adjustments an adequate view is not achieved, withdraw the laryngoscope, mask-ventilate the patient with 100% oxygen, and re-plan. Persisting with a poor view leads to hypoxia.

- Know When to Change Equipment: The ultimate adjustment may be to change the laryngoscope itself—switch from a Macintosh to a Miller blade, or from a direct to a video laryngoscope.

Adjusting a laryngoscope in someone's mouth is the core skill of laryngoscopy. It is a dynamic, cognitive, and tactile process that translates theoretical knowledge of airway anatomy into practical success. The adjustments—axial lift, tip repositioning, rotational torque, and external manipulation—are a limited but powerful set of tools. Their effective application requires a systematic approach: optimize the lift first, fine-tune the tip position, control the tongue, and finally, manipulate the larynx externally if needed. In the era of video laryngoscopy, adjustments become more about camera navigation and less about brute force, but the principle of using visual feedback to guide mechanical correction remains paramount. By mastering these adjustment techniques, clinicians move beyond simply inserting a laryngoscope to truly wielding it with precision, thereby ensuring the highest likelihood of securing the airway safely and efficiently on the first attempt.

Contact us to get more information!

If you are using a Macintosh blade and can only see the epiglottis (a Grade IIa view), the most critical and first adjustment is to significantly increase your axial lift. In most cases, the blade tip is correctly placed in the vallecula, but you are not applying enough upward-and-forward force to fully elevate the epiglottis via the hyoepiglottic ligament. Focus on lifting from your shoulder and arm with a straight wrist, ensuring you are not rocking on the teeth. A stronger, proper lift will often convert a Grade IIa view to a Grade I view.

This "can't intubate, can oxygenate" scenario with a good video view requires adjustments to your tube delivery, not necessarily the laryngoscope itself.

- Adjust the Stylet Shape: Ensure your stylet has a more pronounced "hockey stick" curve that matches the blade's angle.

- Adjust the Tube Introduction Point: Start the tube from the extreme right side of the mouth. If it's getting hung up on the right arytenoid, try starting it more midline.

- Use the Tube as a Tool: Under screen guidance, use the tube tip to gently lift the epiglottis if it's still下垂.

- Withdraw the Blade Slightly: Sometimes a minimal withdrawal of the laryngoscope blade creates more space for tube manipulation.

The key is to watch the tube tip on the screen and make small steering adjustments as you advance.

You should withdraw the laryngoscope and re-oxygenate the patient if:

- You have made multiple logical adjustments over 20-30 seconds without improving the view.

- The patient's oxygen saturation begins to drop.

- You feel yourself becoming frantic or applying excessive force.

- You realize the blade size or type is clearly wrong (e.g., a Macintosh 4 in a small adult).

Persistence with a failing technique is dangerous. The safe adjustment is to abort the attempt, ventilate, re-assess, and prepare for a fresh attempt with a new plan, which may include a different laryngoscope.

Prominent upper incisors require careful technique to avoid damage.

- Initial Insertion: Insert the laryngoscope blade even more carefully from the far right corner, almost parallel to the teeth, to avoid scraping.

- Lift Adjustment: Your lift must be perfectly axial, with zero rocking. Consider using a blade with a thinner profile (e.g., a Miller) or a smaller Macintosh blade.

- Use a Tooth Protector: A commercial tooth guard or a folded piece of rigid Styrofoam can be placed over the upper teeth.

- Leverage Point: Be consciously aware that your fulcrum is the mandible, not the maxilla. The force should lift the mandible, not press on the upper teeth.

Yes, pediatric adjustments require extreme gentleness and precision.

- Force: The required lifting force is minimal. Excessive lift can easily injure delicate tissues.

- Blade Choice: Straight blades (Miller) are often used, so the adjustment is direct tip placement under the epiglottis.

- External Manipulation: ELM is performed with a single fingertip, applying minuscule pressure.

- Anatomy: The epiglottis is larger and more floppy, and the larynx is more anterior and cephalad. Fine, millimeter adjustments of the blade tip are the norm. The principle of using the laryngoscope to lift the mandible and tongue, not to lever, is even more critical.

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493224/

[2] https://www.thoracic.org/professionals/clinical-resources/critical-care/clinical-education/airway/direct-laryngoscopy.php

[3] https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/safety-standards-quality/guidance-resources/airway-management-guidelines

[4] https://www.apsf.org/article/evolution-of-airway-management-video-laryngoscopy/

[5] https://journals.lww.com/ejanaesthesiology/fulltext/2021/12000/video_laryngoscopy__past__present__and_future.4.aspx

[6] https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/guidelines-for-airway-management

[7] https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/surgery-devices/laryngoscopes