Content Menu

● Foundational Principles and Pre-Use Preparation

>> Understanding the Objective

>> Pre-Procedure Preparation: The "Fail to Prepare, Prepare to Fail" Adage

● Step-by-Step Procedure for Direct Laryngoscopy

>> Patient Positioning: The "Sniffing Position"

>> The Technique: A Deliberate Sequence

● Step-by-Step Procedure for Video Laryngoscopy

>> Positioning and Preparation Variations

>> The Technique: Leveraging Technology

● Specialized Applications and Scenarios

>> The Difficult and Failed Airway

>> Use in Emergency and Pre-Hospital Settings

● Post-Procedural Considerations: Device Care and Documentation

● Common Errors and How to Avoid Them

● Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

>> 1. What is the most important single tip for successful direct laryngoscopy?

>> 2. When should I choose a video laryngoscope over a direct laryngoscope?

>> 4. How do I manage excessive secretions or blood in the airway during laryngoscopy?

>> 5. Is it acceptable to use a laryngoscope for purposes other than endotracheal intubation?

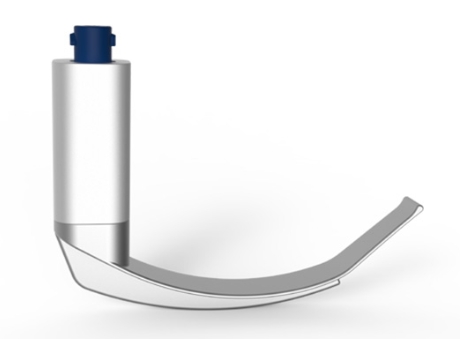

The laryngoscope is a quintessential instrument in modern medicine, primarily employed to visualize the larynx and facilitate endotracheal intubation—the placement of a breathing tube into the trachea. Its use spans critical scenarios from planned surgical anesthesia to emergency resuscitation. While the fundamental purpose remains constant, the technique for using a laryngoscope varies significantly between the traditional direct laryngoscope and the advanced video laryngoscope. Mastering the use of this device requires not only manual dexterity but also a deep understanding of airway anatomy, patient positioning, and the specific mechanics of the tool at hand. This comprehensive guide details the step-by-step procedures, critical nuances, and clinical decision-making involved in the proficient use of a laryngoscope for securing a patient's airway.

The primary objective of using a laryngoscope is to obtain an unobstructed view of the glottic opening—the space between the vocal cords—to allow for the safe passage of an endotracheal tube. Whether using direct or indirect visualization, every action with the laryngoscope is directed toward this goal.

Before even touching the patient, a systematic preparation phase is crucial:

1. Device Readiness Check:

- For a direct laryngoscope: Verify the light source is functional and bright. Check that the blade securely locks onto the handle. Have multiple blade sizes (e.g., Macintosh 3 and 4, a Miller blade) immediately available.

- For a video laryngoscope: Power on the device. Confirm the battery is charged. Check that the camera lens is clean and not fogged (activate any anti-fog feature). Ensure the display is active and providing a clear image. Have both standard and hyperangulated blade options ready if applicable.

2. Patient Assessment: Perform a rapid airway assessment (Mallampati score, thyromental distance, mouth opening, neck mobility) to anticipate difficulty and inform blade choice.

3. Gathering Ancillary Equipment: Have the appropriately sized endotracheal tube with a stylet (shaped for video laryngoscopy if needed), a 10ml syringe for cuff inflation, a stylet, a suction catheter with Yankauer tip, and confirmation devices (e.g., capnograph, stethoscope) ready and within reach.

4. Pre-oxygenation: Administer 100% oxygen via a facemask for at least 3 minutes (or 8 vital capacity breaths in an emergency) to denitrogenate the lungs and create an oxygen reservoir, prolonging safe apnea time.

Optimal positioning is paramount for direct laryngoscopy. Place the patient's head on a firm pillow or pad to flex the lower cervical spine, and then extend the head at the atlanto-occipital joint, bringing the face to a horizontal plane. This "sniffing the morning air" position aligns the oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal axes into a more direct line, making the path from the lips to the glottis as straight as possible.

1. Opening the Mouth and Blade Insertion: Stand at the patient's head. Use your right hand to open the patient's mouth using a "scissor" technique (crossed thumb and index finger). With your left hand, hold the laryngoscope handle like a pen. Insert the blade from the right corner of the mouth, carefully avoiding the teeth and lips.

2. Sweeping the Tongue: As you advance the blade, use its flange to sweep the tongue to the left. The tongue must be completely controlled within the left side of the blade's flange; if it escapes back into the visual path, the view will be lost.

3. Advancing to the Landmark: Gently advance the blade along the contour of the tongue until you identify the epiglottis. For a curved Macintosh blade, advance the tip into the vallecula (the space between the base of the tongue and the epiglottis). For a straight Miller blade, advance the tip beneath (posterior to) the epiglottis.

4. The Critical Lift: This is the most important maneuver. Lift the entire laryngoscope upward and forward along the axis of the handle, at approximately a 45-degree angle to the patient's body. The force should come from your shoulder and arm, with a straight wrist. Never use the teeth as a fulcrum to rock the blade. The lift tenses the hyoepiglottic ligament, which elevates the epiglottis and reveals the vocal cords.

5. Visualization and Tube Passage: Once the glottis is visualized (noted as a Grade I-IV view), your right hand passes the endotracheal tube from the right side of the mouth, through the vocal cords under direct vision, until the cuff passes 1-2 cm beyond the cords.

6. Confirmation and Removal: Inflate the cuff, confirm correct placement with continuous waveform capnography (the gold standard), auscultate for bilateral breath sounds, and observe chest rise. Only then do you carefully withdraw the laryngoscope blade along the path of insertion, being careful not to dislodge the tube.

Patient positioning for video laryngoscopy is often more flexible. A neutral or "sniffing" position is typically adequate, as the device does not rely on axis alignment. The key is to ensure the display screen is positioned comfortably in the operator's line of sight.

1. Insertion with Screen Guidance: Hold the video laryngoscope in your left hand, but keep your eyes on the display screen from the moment of insertion. Use the real-time video feed to navigate the blade past the tongue, using it as a visual roadmap. There is less reliance on the "blind" sweeping maneuver.

2. Navigating to the Glottis: Gently advance the blade, using the screen to identify anatomical landmarks: the uvula, the epiglottis, and finally the arytenoid cartilages and vocal cords. The goal is to center the glottic opening on the screen.

3. Optimizing the View: With a video laryngoscope, minimal lifting force is often required. The focus is on fine adjustments—slight rotation, advancement, or withdrawal—to achieve the best possible camera view. The "lift" is more about positioning than forceful displacement.

4. Tube Delivery (The Key Difference): This step varies by blade design.

- With Standard Geometry Blades: Similar to direct laryngoscopy, the tube can be passed under indirect video guidance.

- With Hyperangulated Blades: The tube must be pre-shaped with a stylet into a pronounced "hockey stick" curve. The operator then guides the tube tip into the screen's view and carefully navigates it around the blade's curve and through the vocal cords. This often requires watching the tube itself pass rather than maintaining a static view of an open glottis—a technique called "following the tube."

5. Confirmation and Withdrawal: As with direct laryngoscopy, confirm tube placement definitively with capnography before removing the laryngoscope.

Using a laryngoscope on infants and children requires extreme precision. Straight blades (Miller) are often preferred due to the large, floppy epiglottis. The lifting force must be minimal to avoid trauma. The video laryngoscope is particularly valuable in pediatrics for its magnified view and reduced required force, but specialized, smaller blades are essential.

The laryngoscope is central to both predicting and managing difficult airways.

- Anticipated Difficulty: Based on the pre-assessment, a video laryngoscope is often the first-choice tool. A strategy should be in place, which may include having a second, different type of laryngoscope ready, as well as supraglottic airway devices and cricothyrotomy equipment.

- Failed Direct Laryngoscopy: If a Grade I view cannot be obtained with a direct laryngoscope after two optimal attempts, the strategy should pivot. This is a classic indication to switch to a video laryngoscope, which may provide a view where the direct laryngoscope could not.

In chaotic environments like an emergency room or ambulance, the principles remain the same, but efficiency is paramount. The video laryngoscope offers advantages here, as it can be faster for those proficient with it, provides a shared view for team coordination, and performs well in suboptimal patient positioning often encountered in emergencies.

Proper reprocessing of the laryngoscope is a critical part of its use cycle to prevent cross-infection.

- Blades: Detach and clean immediately. Disposable blades are discarded. Reusable blades undergo thorough manual cleaning followed by high-level disinfection or sterilization.

- Handles: Wiped down with a disinfectant. For video laryngoscope handles, strict adherence to manufacturer guidelines is required; most are not immersible and require specific wipes to avoid damaging electronics.

- Batteries: Recharged or replaced.

Documentation in the medical record should include: the type of laryngoscope used (e.g., "Video laryngoscope with hyperangulated blade"), the blade size, the grade of view obtained (Cormack-Lehane grade), the size of the endotracheal tube, and the number of attempts.

1. Poor Patient Positioning: Leads to immediate failure. Always take the time to optimize the "sniffing position" for direct laryngoscopy.

2. Using the Teeth as a Fulcrum: The "rocking" motion. Focus on lifting along the axis of the handle.

3. Incorrect Blade Size or Type: Leads to poor visualization. Always have alternatives ready and reassess after a failed attempt.

4. Persisting with a Failing Technique: After two failed optimal attempts with one device or technique, change something—the operator, the blade, or move to a video laryngoscope.

5. Neglecting Confirmation: Never assume the tube is in the trachea based on visualization alone. Capnography is mandatory.

The use of a laryngoscope, whether direct or video, is a symphony of prepared technique, anatomical knowledge, and controlled execution. It begins long before the blade enters the mouth, with thorough preparation and assessment, and continues through a deliberate sequence of positioning, insertion, visualization, and tube delivery. The direct laryngoscope relies on precise mechanical leverage and axis alignment, while the video laryngoscope leverages digital imaging to overcome anatomical barriers. Proficiency with both is the hallmark of a competent airway manager, as each has its place in a comprehensive airway strategy. Ultimately, the safe and effective use of a laryngoscope is not just about operating a device; it is about applying a disciplined, adaptable methodology to secure one of medicine's most vital objectives: a patent airway. Through continuous practice, adherence to fundamental principles, and intelligent adoption of technological advances like the video laryngoscope, clinicians can ensure this procedure is performed with the highest possible success rate and safety for the patient.

Contact us to get more information!

The most critical tip is to lift along the axis of the laryngoscope handle, not rock on the teeth. Successful visualization depends on using the blade to lift the tongue and epiglottis forward, which requires force directed from your arm and shoulder in an upward and forward vector (like lifting a suitcase). Using the upper teeth as a pivot point (rocking) fails to achieve this lift, damages teeth, and should always be avoided.

A video laryngoscope should be strongly considered as the first choice in: anticipated difficult airways (based on pre-assessment), unanticipated difficult airways after a failed direct laryngoscopy attempt, scenarios with limited neck mobility (e.g., cervical spine precautions), cardiac arrest (where it can minimize interruptions in chest compressions), and for teaching (as it allows shared visualization). Many institutions now advocate for its use as a first-line tool for all intubations due to higher first-pass success rates.

This is a common experience, especially with video laryngoscopes using hyperangulated blades. You have a "great view but can't get there." The causes are often:

- Tube Shape: The endotracheal tube is not pre-shaped to match the curvature of the blade.

- Tube Position: The tube is introduced in the wrong part of the mouth (e.g., too far right) and hits the arytenoids or vocal cords laterally. Try introducing the tube from the far right corner of the mouth or using the screen to guide the tube tip centrally.

- Lack of Stylet Support: A malleable stylet is essential for steering with hyperangulated blades.

This highlights that laryngoscopy involves two separate skills: obtaining a view and then successfully delivering the tube through that view.

Secretions and blood are the enemies of clear visualization. The strategy is suction, suction, suction. Have a Yankauer suction catheter in your right hand or held by an assistant before you insert the laryngoscope. If the view is obscured, briefly pause, insert the suction catheter into view under direct or video guidance, clear the fluid, and then continue. With a video laryngoscope, you can often suction under direct screen guidance. Do not attempt to blindly pass a tube through a pool of secretions.

Yes, the laryngoscope is a versatile visualization tool for the upper airway. Common alternative uses include: diagnostic examination of the larynx and vocal cords, foreign body removal from the hypopharynx, assisting with the placement of a nasogastric or orogastric tube (by visually guiding it into the esophagus), and aiding in difficult upper GI endoscopy. In these cases, the technique focuses on gentle exposure and visualization rather than the forceful lift required for intubation.

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493224/

[2] https://www.thoracic.org/professionals/clinical-resources/critical-care/clinical-education/airway/direct-laryngoscopy.php

[3] https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/safety-standards-quality/guidance-resources/airway-management-guidelines

[4] https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/guidelines-for-airway-management

[5] https://www.apsf.org/article/evolution-of-airway-management-video-laryngoscopy/

[6] https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/surgery-devices/laryngoscopes